The Long Goodbye

Before you go, what if you stayed?

In Midwestern culture, it’s a staple of connection. It does not matter who the foyer belongs to — friend, family, lover, or other — you’re going to hover before you leave. In the winter, when extra accouterments are required to brave what awaits you on the other side of the door, that lingering extends even further.

There’s the weather, the news, maybe some gossip you didn’t get to during dinner or drinks, or whatever you were doing before that goodbye. It’s one of those traditions you hate as a kid but understand and love, even when you’re the deciding party.

Choice, decision, freedom.

I’m home from New York, eating at a crappy diner with my grandpa, the first time he mentions that he is ready to die. He’s 89. It’s a casual declaration, said in between bites of over-scrambled eggs and under-salted veggies. “I get it, man,” I tell him, uneasy but understanding. And I do, really, get it. Grandma passed a few years ago. She had a rare form of breast cancer, but that isn’t what killed her. She was sick for 15 years, but she died in 4 days.

It was a miracle she made it that long. IBC doesn’t always show up on a mammogram. Her doctor had a hunch, and his hunch gave her another decade, at least. Which meant she spent a decade closer to my mom. Which was all worth it — the twice-broken hip (both on Thanksgiving, six years apart), the tough years of chemo, and the inevitable but swift end. Peaceful, it was peaceful. She died in her sleep, with my mother holding her hand.

Those are the easy ones. Where modern medicine proved it is nothing short of a marvel. My paternal grandmother passed within weeks of my maternal grandmother. I loved her immensely. I wear her curls in my reflection. She was piss and vinegar. A dirty cheat at cards with a heart of gold.

She got sick in months, but carried the dementia with her for years. Mainly confined to a small room, sometimes shared, her passing was a slow dissolve. Once, on the car ride home, I caught my Dad trying to hide a prayer under his breath. “I hope she never forgets my name.”

And she does, on the bad days. Where sons become fathers or cousins. Grandchildren become sons or husbands. “They’re moving me upstairs,” she tells me with glee. But there is no upstairs. Dad thinks she means Heaven. I nod to agree.

I wasn’t there for the last Christmas, but my brother tells me they wheeled her out — delirious and afraid — as a ceremonial goodbye of sorts. Everyone got to hug her, or you know, sorta put their arms around her.

And I’ll never question the nurses or my lovely family, who provided close care to her in those final few years. But maybe I am curious about the system. One that has perfected the art of keeping someone alive, if only barely, to be brought out like an ornament at Christmas.

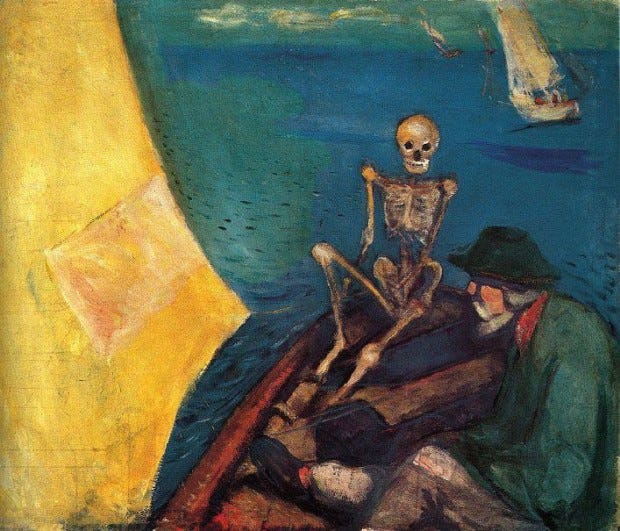

So it all feels novel when, at dinner, of course, because there’s always a table setting for this kind of news, my mom tells me that my grandfather has chosen to die. The science is simple. Once he stops his dialysis, a daily 10-hour journey, he will live a month, tops. Weeks, most likely.

His body can’t break down the toxins on its own, so it’s good for him to eat. I bring him chocolate-covered peanut clusters, a favorite of ours. We eat them in conversation. He’s still lucid. He’ll be 92 on October 7th, if he makes it. I’ll be 29, on the 11th. He wants to celebrate, but he’s not making any promises.

He died in the comfort of his own bed during the night of September 10th. Just the way he had requested. In control. Like grandma. Peaceful.